Using data narratives and participation to open government | The Making of Common Ground

Common Ground is the New South Wales Government’s first community focussed open government web service, designed to help people easily access information about current exploration and mining activities in their area.

Internationally recognised as best practice in open government, I am often asked about how it came about. Here is our story — an in-depth article of how government can be open and participatory by design.

Common Ground is a mobile web application providing people with easy access to interactive maps and details of current and proposed coal, mineral, petroleum and gas activities across the Australian state of New South Wales.

It brings together a wide range of information: location data; data visualisations; explanations of how decisions are made (the project development and approval process); who is involved; and links to company operations and environment reports. It allows people to search location, companies, and resource titles; and share search results with others via social channels or government enquiry service.

NSW has a long history of gold, minerals, and coal mining. Supporting the extractive industries and its expansion to boost our economy, has been a prime focus of Government over the years.

Common Ground was created in response to community criticism of the NSW Government, in not addressing concerns and lack of communication with the general public about the coal seam gas industry, coal mine expansions, and other mining issues.

Open cut coal mine Hunter Valley, NSW. Image source: NSW Department of Industry

Social Context for Change

In 2010, it was revealed that a coal seam gas exploration licence had been approved in St Peters, an inner city suburb 7 kms from Sydney Harbour (which is also less than a km from where I live).

The press discovered and reported that the exploration company had not adequately consulted the local community. People living next door to the proposed site and neighbours in the surrounding areas knew nothing about it.

This situation exposed the lack of transparency, consultation, and information about the Australian gas industry. People wanted to know how a coal seam gas exploration licence covering a large part of the Sydney Basin and Sydney’s central business district, could be approved without people knowing or being alerted and consulted by the company, or the NSW Government.

Petroleum Exploration Licence 463. Source: http://www.resourcesandenergy.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/image/0005/553487/PEL-463.jpg

In 2011, the coal seam gas industry was well established and growing in Queensland and rural areas in NSW. The ABC produced a story and website called Coal Seam Gas By The Numbers showing locations of licences and wells in place at the time, water usage data and content explaining the fracking process.

Around this time, Gasland, the documentary about the US shale gas industry had been released. People across NSW became angry, frustrated and scared.

People started discovering coal seam gas exploration applications and licences in their communities. They got angry too.

The issue was creating unlikely alliances. Farmers and environment groups, who had previously been on opposite sides, were joining forces. Community organisations such as Lock the Gate and Stop CSG were gaining traction in areas where activism had not previously existed. People old and young got involved.

Coal Seam Gas protest, Illawarra, NSW. Image Source: Stop CSG

Background — How Common Ground came about

In 2011 the NSW Department of Trade and Investment hosted an event called Collaborative Solutions Mobile Government. It was an innovation scheme to encourage ICT (information, communications, technology) service providers to come up with ideas to assist government agencies improve their services using mobile technology. I wasn’t strictly ‘ICT’ at the time, but I was invited because I’d worked in the film and visual effects industry, and been producing mobile content since 2008.

The Executive Director of Minerals from the Division of Resources and Energy, and a Team Leader of the Geoscience Information Program, presented at the event and spoke of the need to better communicate with the general public about coal seam gas using their geospatial data (maps).

Innovation happens when new voices are heard and fresh ideas are supported.

I met with Geoscience Information team and pitched them the multi-platform interactive documentary series that I had been developing. My objective was to create community focussed content about: the origins and life cycle of different natural resources to show the value chain; explainers about exploration, mining and production processes; and local content to help people understand how government decisions were made.

The Collaborative Solutions initiative wasn’t suited to funding the department’s project or mine. However, it was extremely helpful in facilitating a connection. In 2012 they engaged me as a Creative Technologist to research, scope and help develop some educational and communications projects — including an exhibition installation and a prototype of an online ‘community map portal’, which became Common Ground.

The Stop Coal Seam Gas human sign at Austinmer in 2011. Image source: Bulli Times.

Political Will Makes Innovation Happen

In 2012, the community concern and media coverage about the coal seam gas industry and mining licence allocations reached a significant peak.

Eddie Obeid, a former NSW Minister for Resources under the previous Government, was facing the NSW’s Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) investigation related to a coal exploration licence granted in June 2009 over the farm and two adjacent properties, in which he and his family had an interest. Another former Minister, Ian MacDonald, was also implicated.

The Minister for Resources in 2012, Christopher Hartcher, and the NSW Government wanted a better way to communicate to the general public about exploration, mining and production titles. The staff at the Division of Resources and Energy were also being inundated with enquiries.

The web app prototype we’d made between March and June 2012 using the department’s mapping data gathered enough high level support to get approval to go into production in October 2012.

The idea had been championed by the Executive Director of Minerals and the Team Leader from the Geoscience Information unit of the Geological Survey of NSW. An internal team was established and comprised of a Project Owner, Project Leader, Project Board (made up of representatives from the Division’s units who were the content and data custodians), and a Project Manager.

I was engaged as an external Producer/Creative Director to manage design, content and community engagement on the project. I designed a collaborative approach, and established a team of small businesses and specialists who were engaged to provide research, design, accessibility expertise, and web development services.

An initial timeline of 6 months was given to deliver a solution (October 2012 — May 2013). The budget for the projected 6 months was about $650,000 and was funded out of the NSW Government’s New Frontiers Initiative. Very early on it became clear that the proposed timeline was unrealistic. The department needed more time to engage ICT developers through a request for quote procurement process, and arrange access to the data we needed. The benefit was it allowed us to do meaningful research to inform the design and development.

The project was re-scoped to provide time for considered research and engagement with community and other stakeholders, and to establish the participatory design approach, which was revolutionary for government.

The Existing Information Experience (Our Content Challenge)

Many people we encountered believed the government was hiding the information they were looking for. The reality was its old ‘legacy’ and outdated systems were inaccessible and unusable by most people.

The existing government services were also designed to provide information to industry. The services were difficult to find, use, and understand. ‘Special knowledge’ was needed to use maps and systems where company documents were kept.

The government wasn’t purposefully hiding things, it had a content design problem.

Information was disconnected. People had to go to multiple places to find what they needed and to make sense of the data presented to them. What little content existed for the community, was written in jargon or legalese.

The industry bias led to community frustration and a perceived lack of transparency by the government.

The general public didn’t understand what the data on the maps meant. It led to confusion, misinterpretation, and misrepresentation of information.

The existing maps systems presented information in a way where it looked like almost all of NSW was going to be ‘mined’. These maps were being distributed throughout communities without context or explanation of what the title layers meant.

NSW Government’s Minview, active mining and production titles 1 October 2014.

Many documents of great interest to community members and environment groups were already ‘open’ and available: company approval letters, exploration and mining licences, mining operations reports and review of environmental factors reports (REFs). The information was difficult to access (unless you knew the exact combination of title or tenement number to use), and was at times incorrect.

DIGS database managed by NSW Geological Survey.

Information to explain what the title codes and acronyms meant were in documents not suited to the general public. If you wanted to find what a PEL (Petroleum Exploration Licence) or a PSPApp (Petroleum Special Prospecting Authority Application) meant, you had to search legislation and multiple Mining and Petroleum Acts.

Petroleum (Onshore) Act 1991 No. 84

When I started work, I asked a lot of questions about the meaning of things and how things worked. The frequent responses were “why do you need to know that?” and “people won’t be interested in that”.

There was a need to change the culture of assumed knowledge in government.

Gradually people in the department started seeing their content from a different perspective, and understanding why their information was important for the community and needed translation.

Project Objectives

Improve communications, openness, and transparency.

We wanted to provide easy access to information and locations of mining activities to help build trust in government.

Embrace open government principles.

In 2012, the Premier of NSW Barry O’Farrell had issued a memorandum and commitment to open government. It was inspirational, however, aside from the open data portal and a community of practice, not much else was happening. I discovered very few people knew about it and many government staff I encountered, were dismissive of it.

Common Ground was the perfect opportunity to deliver on the promise of open government. So, I embedded this philosophy into our design process.

Increase accessibility using a mobile first design approach.

People wanted access to current information via mobile phones, tablets and PCs. In 2012, the majority of government websites and location services were not designed for mobile, nor were they responsive (able to adapt to different device screen sizes and browsers).

The trend at the time was to make ‘native’ mobile applications (Apple or Android apps), which are not accessible for all internet users, and operationally and financially unsustainable for government.

We wanted to make a location aware service so people could search what activities were happening around them using GPS technology.

Rather than a website, we needed to build: a web service that could access current data from different places and government departments; and a responsive mobile web application with an engaging interface and easy way for people to interact with and search data.

Create new ways of working.

The traditional government ICT procurement approach was to: write a brief, send a request a quote or publish a tender to ‘market’. The market being a small group of preselected companies on a closed ‘panel’ of preapproved government service providers. Usually a single ‘IT vendor’ was engaged to build a fixed price solution ‘at arm’s length’ to their government clients.

The way procurement was done did not allow for opportunities for research and discovery phases, or diversity, such as collaborations with small businesses or a wider range of new service providers. The procurement approach was lengthy, required a lot of documentation, and tenders were often based on the premise that a solution already existed.

Briefs and other procurement documents were written without government staff really understanding; the problem, what was required to make a customer facing web service, their audiences and their needs, or contribution from the people who the service was meant to be designed for.

We researched existing local and international solutions and did comparative and precedent analyses. ‘Out of the box’ geospatial (mapping) and existing location services were not designed for citizens and non-expert users, or mobile phones. Nor did these solutions have ways to incorporate the contextual content and explanations our community audiences needed.

Our project leaders wanted to do things differently, experiment, and make something fit for purpose. They were under pressure, and were expected to move fast.

Understand what the community actually needed.

When we made the prototype in 2012, I was the only ‘community’ person in a room of 12 government staff and 3 software developers, providing insights and ideas from an outside perspective.

Staff at the department were overwhelmed with dealing with community frustration and discontent. At the time they were reluctant to talk to people who were angry at the Government and confrontational with them. To design for a community audience, we needed to talk to them directly, and other ‘stakeholders’ connected to the issue. Especially, local activists and environment groups.

Social Issue Service Design

In 2012 there was a stand-off between the industry, communities and the NSW Government. Each had different expectations and wanted different outcomes. To be able to build trust, a big challenge for us was understanding, addressing and wrangling everyone’s needs.

The stakeholder engagement, collaborative, and participatory design methods I proposed were bravely embraced by our project leaders.

Participatory Design

Over 150 people from the community, government and industry were directly engaged in the design and development process. At the time this aspect of the service design was unique. It was extremely well received and essential for making sure we could design what people needed, research and improve content, and test the usability of the service.

Participants were from urban and rural areas; individuals, Aboriginal landowners, environment groups, activist groups, farmers, explorers, miners, mining and agricultural companies and associations, community consultation committees, federal agencies and local councils.

The range of people who participated in making Common Ground

People participated in the design process at every stage of the project. From early user research, paper prototyping, through different design iterations and improvements, until the public beta version in 2014.

Individual interviews and group feedback sessions provided an opportunity to gather rich and meaningful insights such as:

content needs, language, and different interpretations of jargon

usability, functionality

suggestions for additional data and map layers

communications channels people used

what people wanted to do and expected to do with the information

other people/organisations we should connect with to test and promote the service

excellent ideas on presenting and connecting content, local stories, and interesting use cases

The Division of Resources and Energy’s offices were located 3 hours’ drive north of Sydney (in the Hunter Valley). We set-up a ‘pop-up’ project office above a cafe called Fleetwood Macchiato in Sydney’s Inner West suburb of Erskineville, very close to public transport. This lo-fi space created a comfortable and neutral space for people to visit us, and we had an endless supply of willing participants when we needed to test usability or content.

Many internal government staff and the project board were integral to the making and testing of the service. Despite us working mostly remotely, our core service design team travelled north to collaborate closely with them, to wrangle content and data, and to ensure the service design supported their needs too.

Agile Development and Continuous Improvement

Our small team of multi-disciplinary service providers worked fast and in parallel to try to meet the shifting project deadlines and manage hiatuses. Resources were limited.

Our approach was collaborative, participatory, agile, and pioneered a new way of building government services.

Historically, IT and government web projects work to a very specific set of requirements and documentation in fixed scope ‘waterfall’ model and release a product or service when it is complete. This design process was rigid and projects took a long time to get to market.

Common Ground production story, illustrating the different concurrent work streams. It might look like a ‘waterfall’ schedule — it’s not. Within some streams are small cycles and multiple iterations.

Agile development had become a proven method, popular in digital visual effects and animation film production, start-ups, and many large successful technology companies (Facebook, Twitter etc.).

The intention of agile development is to produce software services to reach target audiences quickly. Responsive to change, ‘chunks of work’ are identified based on user needs, teams work collaboratively to build the service and continually test, adapt, and iterate, based on feedback from people using the service and stakeholders.

The UK’s Digital by Default Strategy and Government Digital Services led the way by introducing ‘agile’ in 2011. It also fostered a citizen-centred design and stronger engagement with small and medium size companies. Agile development has now been adopted by Australian Government’s Digital Transformation Agency (formerly DTO) and other state agencies.

Whole of Government Thinking

From the general public’s perspective the Government is one entity.

Many government agencies are integral to, or involved in, the decision making process for mining and production exploration and production approvals, regulation, and governance.

In order to ensure data and content was relevant, accurate, and current, it was crucial for us to connect directly with the custodians of the information.

Initially there was a reluctance to engage with other agencies, the fear being it would slow things down. Not engaging was not an option. We needed them.

Finding the right people did take time, and perseverance. As an outsider, the lack of interagency communication channels and basic information was surprising. Once we found the right people to talk to, they were incredibly helpful and things moved quickly.

Through this experience we have a good understanding of the complexity and challenges around data sourcing, interagency engagement and collaboration. We had the benefit of being ‘outsiders’ and were able to build bridges between the silos that existed at the time and bring a fresh perspective.

Once involved, other agencies such as Department of Planning, Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water, Office of Coal Seam Gas, were very supportive of the project and contributed data, content and ideas.

Designing Government Data Stories

Governments are custodians and publishers of vast amounts of data and content in varying formats, made for many audiences, and uses.

A number of NSW Government services already showed the data we had access to. Our point of difference was the content design; how the data was presented, filtered, curated, interpreted, explained, able to be discovered and shared.

People don’t have to be experts in mapping, mining or geology to be able use Common Ground.

To help make mining and production easier to understand for our community audience, we took a storytelling approach.

Common Ground web app home page

Making Meaningful Content

Our research showed that the general public found information about mining and the coal seam gas industry confusing and overwhelming. They wanted to know how the industry works and how decisions are made. They didn’t know what a mining or production title is, therefore they didn’t understand what the maps, acronyms or boundaries meant. So we created content to simply explain it.

Content themes were informed by our research and tested by our participants.

Data Interpretation — Cracking the Content Structure

Government and industry are familiar with the multitude of interchangeable terms and acronyms used to describe and categorise titles (e.g. application, authorisation, licence, lease, tenement or concession).

In NSW there were 36 ‘active’ on-shore applications and titles, each with different acronyms, rules, and regulations. We had to categorise them in a way that helped our audience access the information they wanted.

To add to the complexity, naming is not consistent across government departments. Each Australian state (and other countries) use different terms and ways to categorise resource and energy information and projects too.

People in local communities wanted to search for terms like ‘coal seam gas’ or ‘CSG’ however, the data provided didn’t use this language. To geologists and law makers coal seam gas is defined as a hydro carbon and labelled ‘petroleum’. Our community audience would not know to use this term to search for CSG. We ensured the audience appropriate language was used and provided educational content to explain resource groups and definitions.

People also wanted to be able to find exploration activities and existing operations. The data didn’t reflect the stages of a project either.

Data is content.

On projects like this, everyone needs to be part data scientist/sleuth and do ‘technical’ data analysis to: work out what there is to work with; assess quality; translate; identify where the gaps are; explore opportunities to connect and link data; decide what’s useful and what other data sets can enrich the story, substance and engagement.

Data needs narrative to make it meaningful

In order for us to be able to present the information in a meaningful way for our audience, we used the existing data but had to create our own structure and ways to categorise things.

Our structure was based on the process story; defining the stages in the lifecycle of a mining or production project, from exploration application to a lease permitting companies to operate and extract.

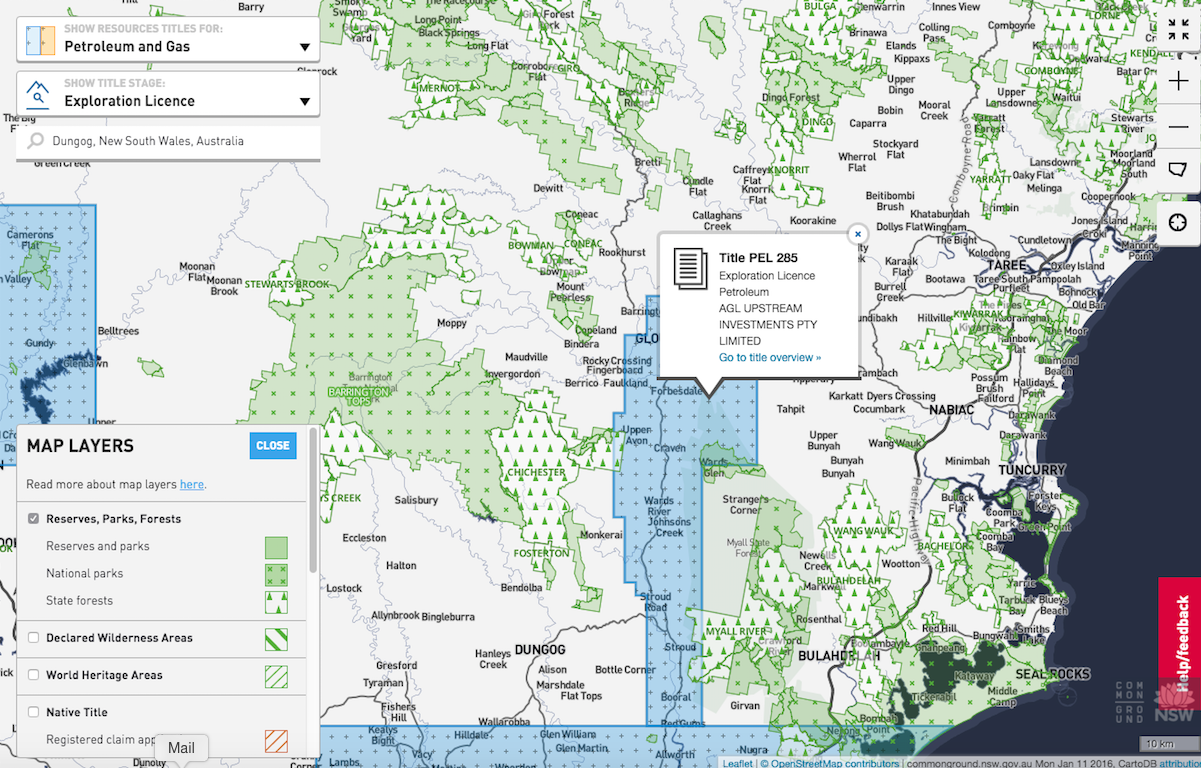

Ways to explore, interact and filter data on the maps

Interactive map showing Mining or Production leases

Information Design

The information and interaction design evolved during the design process as we better understood the data we could access, uncovered what spatial information (maps) and other content people wanted to see, and in what context.

Features:

interactive maps are searchable by location, resource type, stage of a project, company name (main title holder), application and title numbers

map layers such as National Parks, State Forests, Native Titles, Aboriginal Land Councils, locations of mines, gas wells can be shown in context with a resource title

contextual content explains what is appearing on the map

clear explanations of government and industry processes and the role of community in decisions to approve applications and titles

access to environmental reports and company documents

ability to share map and title search results with others via social channels or send enquiries to the department

Map searches present a searchable list of titles leading to more data and contextual content and company information.

Map layers show the context of mining with other land uses and exclusions zones.

Satellite base maps show an established gold mining area overlaid with mining titles and State Forest map layer.

Community Driven Content Design

We designed content to meet community’s needs. All content decisions were led and validated by our research, and written in what’s called ‘plain English’.

Good, relevant, audience focussed content takes time.

Original content was created to explain concepts such as exploration and mining activities. We adapted existing content from Resources and Energy and other agencies, and interpret legislation, policies, mining industry and government jargon.

Content was crowd sourced from; participants, community groups, NSW Farmers, Environmental Defenders Office, Aboriginal Land Council, Native Title Tribunal, NSW Minerals Council, and Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association, and industry.

Writing for mobile forces you to be efficient. We created short concise reusable content chunks to simply explain data and government processes to be published in multiple places.

Writing and editing content for mobile is an iterative process requiring information to be distilled into very short chunks. We continually tested our content to ensure it was clear, and did not lose meaning and accuracy.

Content Style

Our aim was to make Common Ground informative, balanced, current, and accessible.

We were trying to create a neutral place between two extreme spectrums: the desire to drive industry and economic growth through exploitation of resources; and community concerns about impacts on land, community and environment.

Language can engage or alienate people. The choice of words, voice and tone are exceptionally important.

Governments have a tendency to use confusing language and overuse words such as ‘undertake’.

Industry ad campaigns and other government websites showed happy farmers, often with cows next to coal seam gas wells. At the time everyone was presenting different ‘facts’.

To build credibility with our community audience, our intent was to create a distinctive neutral voice, visual language and vocabulary.

Our content strategy was to create useful, educational, and shareable pieces of different kinds of content to help raise awareness and promote the service within government, industry and communities.

Neutrality is reflected in images and words. On Common Ground there are no cows in paddocks. We never use the words ‘facts’ or ‘undertake’.

The Power of Process Pathways

Helping community understand the decision-making process of any potential project and when consultation should occur was a key content requirement, validated by our research.

We took a storytelling approach to explain mining and production in NSW to help people understand the complex decision-making process across all agencies.

Creating a visual language and narrative helps people simply understand their place in the process, and when and where they should have access to information.

The Common Ground process pathway is an overview of the lifecycle of projects from a company perspective. It is also an illustration and interpretation of policy and legislation. It shows the stages, contractual obligations, and steps a company must go through to be able to extract resources.

It was an essential artefact used to inform the interaction design and how to best structure the data to be displayed on Common Ground.

The process pathway used for engagement and design. http://nookstudios.com/process-pathways/

Using Content to Engage and Discover People’s Needs

The process pathway evolved over time. At the beginning of the project we sketched out what we thought the process was.

The process pathway helped us learn what content we needed to explain the ‘whole government’ story, particularly how government departments interacted with each other.

The illustrated pathway poster became a valuable and powerful engagement tool when meeting and discussing the project with internal staff and external stakeholders.

It was incredibly popular with the public, community groups, industry, and within government.

Most frequent responses to the poster were: “I finally understand how this process work” and “I love it” (followed by “can I keep it?”)

Not everyone has access to digital devices or will find information online. The poster was designed to be shared and printed to help promote Common Ground too.

The process pathway (or lifecycle diagram of a project) shows:

Stages of a project

What ‘active’ title type/acronym is related to each stage

Steps shows activities companies must do

Estimates of how long activities should take

Obligations for community consultation and environmental reporting

Where multiple agencies are involved in the process

The interactive version of the pathway has an additional layer of content explaining each step and links to other government websites with richer information.

The pathway captured people’s imagination and its success led to requests to develop illustrations for other processes, specifically for individual resources, planning and environment policies.

We realised its potential as a powerful engagement and educational tool for external audiences. Internally, it became a useful induction tool for government staff, many of whom were unclear of their place in the ‘big picture’ and where to direct community enquiries to.

Visualising Data and Linking Content

Common Ground primarily uses data from the Division of Resource and Energy’s Resource Titles database, which is updated daily. Other spatial data displayed as map layers is sourced from other agencies and industry and updated daily or as required.

Title Overview

This page displays the data used on the maps with concise explanations of its relevance, links to useful educational content within the app, and to other relevant department’s websites.

The documents section on the overview page links to the DIGS database, where open company documents such as licence approvals, review of environmental factors, mining operation plans and coal seam gas well reports are located.

Bringing relevant content from many different sources and agencies into one place is challenging.

We explored trying to link to other agency’s databases where documents used for community consultation such as Environment Impact Statements (Planning & Environment) and Environment Protection Licences (Environment Protection Agency) are kept.

This was unable to be implemented due to the inconsistent naming conventions of title codes and project names across agencies, and due to the limitations of the technology and funding at the time.

State Snapshot

The media and community focus was on coal seam gas. We wanted to represent the whole NSW resource story — and put minerals extraction into perspective too. The state snapshot infographics present a mixture of static and live data.

Wrangling Government Data & Projects

Work on Common Ground started in October 2012. At the beginning of the project we used a ‘static’ titles data set to design, build and test the service.

It took 18 months to access the current and live titles data to technically deliver it for use in Common Ground.

Wrangling data and content has to start early in the design process. Getting internal stakeholders, different divisions, and decision makers within departments engaged, is especially important.

Data analysis should be a team effort. Everyone needs take responsibility for its accuracy, ensure it is interpreted in the right way, understand its potential, and also its limitations. This avoids misunderstandings and the unnecessary undoing of design decisions.

Once we had the titles data in place we increased our engagement with industry and mining companies, who were able to identify anomalies and errors in the data, and offer content ideas (which we put on the list for future releases).

We had proposed creative commons licences for content to ensure it was able to be widely shared (which was common practice with other departments) and the data be open and available for reuse (as was the case with other government services).

Communications Strategy

With the live data in place, in April 2014 we met with the now Minister for Resources, Anthony Roberts, to present Common Ground ‘alpha’ version. His response was:

“This is how government should be, open and transparent. Every state should have one.”

Minister Roberts was very supportive. He requested that prior to release, a communications and launch strategy be put in place. This was music to our ears. We’d identified the need but were told previously this was beyond the scope of the project.

A big issue for the department and the public was the way enquiries were dealt with. Community members were not getting the information they needed or received mixed messages from government staff across different units.

Our research uncovered the frustration of staff being overwhelmed by multiple enquiries, inconsistent responses from different units, and correspondence being stored and archived in places not accessible to everyone. Phone enquiries were not being noted. Staff members and subject matter experts could not easily connect with each other to provide a united response.

We created a way for department’s staff to collaboratively respond to all enquiries through a customer service portal. It would also enable the department to track, measure, and collect data about enquiries to ensure responses were timely and accurate.

Most of the enquiries were location and project specific. People wanted to share maps across different channels.

One click on a map page enables people to email, print, tweet or post to Facebook. This is especially helpful when a land owner contacts the department with an enquiry, or community groups want to share new applications in their area.

The link enables people to see the same information (including map layers) and the intent was to cut through the confusion and help community members and staff deal with enquiries more precisely. For us, this aspect of Common Ground was extremely important to support the needs of our internal stakeholders and staff.

Continuous Development and Improvement

Traditionally government ICT projects delivered by a vendor when ‘complete’, would undergo a quality and assurance phase, and then go into ‘service and maintenance mode’. Projects were budgeted using capital expenditure (cap ex) and the operational expenditure (op ex) allocated, once projects were ‘delivered’, was expected to be low.

The version of Common Ground released was what we called ‘beta’ stage. We had proposed and designed a continuous development plan for the service to include additional data sets and features community and industry wanted, (such as water and environment data), and training and handing over of tasks to internal resources (when established).

This was embraced by the department but funding (operational expenditure) and the question of who in the Government was going to be responsible for the ongoing development of the service was still to be decided.

The biggest risk to government services once delivered, is that funding stops and there is no-one responsible for ensuring it works properly, and content is kept current and relevant.

A continuous improvement model is now expected best practice within the NSW Government. How to approach, budget, and fund agile projects and resource the continuous improvement of services, is still an issue and extremely challenging. This makes it very difficult to create innovative and sustainable services, and provide opportunities for small service providers to continue to work, support and collaborate with internal teams.

Timeline and Release

There were a number of hiatuses during the making of Common Ground, while we waited for data and additional funding to be sought. This was particularly challenging for us small businesses and individual service providers working on the project.

We (the service design team) delivered the beta version of Common Ground in September 2014 and handed over to an internal team.

In December 2014 the NSW Government established a one-off buy-back of petroleum exploration licences (PELs) for titleholders across the state. It provided an opportunity for holders of PELs to surrender their titles.

Common Ground was released to the general public in June 2015.

There were a few contributing factors to its delay including; data issues to be resolved prior to launch, the buy-back scheme work, and the impact of the state election which took place in March 2015 (the government was in caretaker mode and no decisions were made until cabinet appointments were made).

Minister Anthony Roberts was reinstated and became the Minister of Industry, Resources and Energy, which ensured Common Ground was finally launched.

The continuous development approach and other features we had proposed to improve engagement between community and industry have not been adopted. However, in December 2016, eight new data sets (including water) and content were added to the service.

In January 2017 Minister Roberts moved portfolios to become the Minister for Planning. Common Ground is still under the Minister’s wing and recently a new Strategic Release stage has been added to the process, which includes a community consultation phase prior to areas being released for coal, petroleum and coal seam gas exploration.

Collaborators

One of the unique aspects of Common Ground was its collaborative approach.

Many individual staff at the Division of Resources and Energy championed the project and were integral to its creation.

The DRE Executive Director Brad Mullard and our Project Leader Guy Fleming were steadfast champions of the project. Core service design team was producer/designer/creative director (me), designer/developer (Andrea Lau/Small Multiples), designer (Simon Wright) developers (Spatial Vision).

The production team consisted of twenty people providing different skills and expertise over the different phases of the project from foundation research stage to launch.

There were many other people involved in the making of Common Ground who gave their time and knowledge, and continue to support its evolution, for which we are very grateful.

Post Launch

Making Common Ground was an extraordinary experience. It was a great opportunity to experiment and test ideas on delivering openness and participation. We learnt a lot about what’s required to work in a government context and how to help make it safe for government staff to engage and innovate, which we now apply to all our work.

Understanding The Benefits of Being Open

Since making Common Ground, open government has become an established and growing global movement. NSW was a pioneer of many open initiatives that have happened behind the scenes. Common Ground’s launch was low key and it was not widely publicised or promoted. It has, however, gladly survived thus far.

Common Ground demystifies data and government decision making — it provides a platform for information that should be accessible to everyone.

Now Common Ground is out in the public domain, people can see its potential for different local, national and global applications. We are often asked “What if” something like this existed not only for extractive industries but also for things such as government spending, planning, major infrastructure projects, all natural resources, primary industries, environmental data…

For me, all of these government themes are connected. We are rising to the challenge of this ‘what if’ because I think an independent platform to address the multiple social issues and government data challenges could, and should, exist.

For me the question has shifted to us needing to answer … “what happens if we aren’t open?” What is the cost to our society? And impact to our governments, communities, industries, investors, our environment, and our economy, if things are hidden and closed?

Procurement Reform

A new NSW ICT Service Scheme was launched during the project, which included new ‘simplified’ contracts, revised intellectual property terms to attract small businesses and entrepreneurs, and make it possible for us to get on procurement panels.

The initial budget allocated for the project had been $650,000 for six months. At the time of the release two years later, the expenditure across the multiple SME service providers was $1.4 million. What I learnt was by traditional government IT project standards, this is a modest budget. The scope of the project changed as people saw the value in the work and its potential, and our project leaders worked hard to keep the project alive.

Common Ground did not fit the traditional procurement process. The success of the project and the goodwill generated during the making of Common Ground highlighted the need to continue to adapt and improve procurement.

The need to make it easier for government to procure and make innovative and agile projects, prototypes, and proof of concepts addressing specific issues or problems, as well ensure the continuous improvement of services, is still a work in progress.

This is why Nook Studios is now an active advocate for procurement reform, open contracting, as well as extractive industries transparency, and raising awareness for local and global open government initiatives.

International recognition

The Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) featured Common Ground in its 2016 publication International Best Practices in Contract Management — Recommendation for the National Hydro Carbons Commission of the Government of the United Mexican States.

In 2018 Common Ground was featured in the Natural Resource Governance Institute and Open Contracting Partnership report Open Contracting for Oil, Gas, and Mineral Rights: Shining the Light Good Practice

Now that Common Ground has reached a global audience, people are interested in the impact Common Ground has had, who and how people are using the service, and analytics. So are we!

Our next article will cover post-launch impact and stakeholder stories, and what’s happening globally. Sign up for articles here.